The surveys of GASA and other bodies illustrate the hundreds of millions globally who are victims of scams every year. The scale of the scam industry has been illustrated by just one part, the South East Asian scam compounds, which it has been suggested generate $64 billion per year. Scamming is therefore a global business, probably worth hundreds of billions of dollars, which leads to an important question: who is behind such a significant industry?

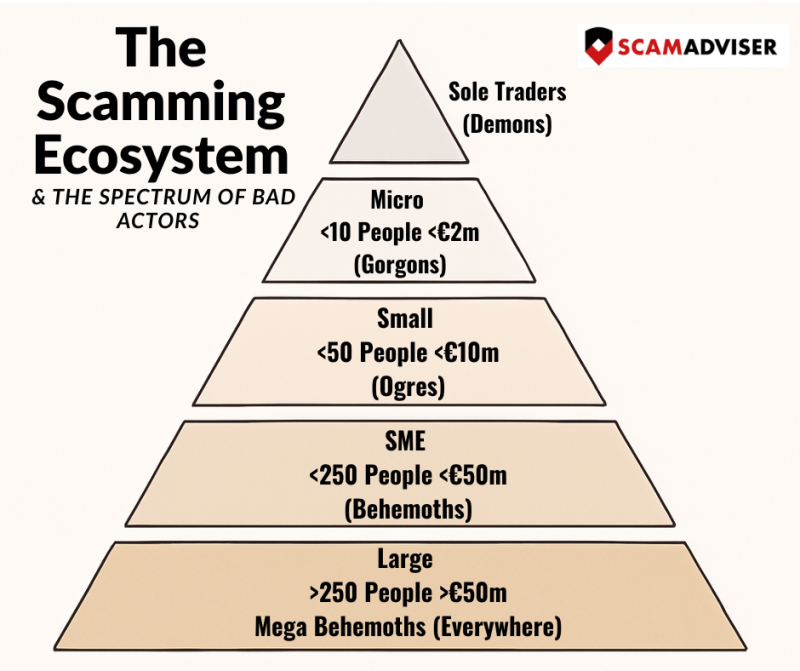

In recent research led by myself for the UK Home Office we have started to comprehend some of the most noteworthy parts of this ecosystem. The following provides an overview using the analogy of mythical creatures and standard business size classifications. It is biased towards the scam industry targeting Western countries, because that was our brief, but we believe it’s a good starting point to exploring the offenders behind the global scam ecosystem.

|

Sole Traders (Demons) |

Micro <10 People <€2m (Gorgons) |

Small <50 People <€10m (Ogres) |

SME <250 People <€50m (Behemoths) |

Large >250 People >€50m (Mega Behemoths) |

| Everywhere |

Everywhere West African Yahoo Boys/ Sakawa Boys/ Brouteurs |

Indian Call Centres West African Yahoo Boys/ Sakawa Boys |

Indian Call Centres SE Asian Scam Compounds |

Indian Call Centres SE Asian Scam Compounds Nigerian Confraternities |

Starting with the smallest, Demons are individuals who operate scams alone. One scammer from Ghana explained to us, “I am alone. I do it alone… I learnt it on my own.” A local investigator agreed, noting most fraudsters are individuals or in syndicates of up to four. A South African law enforcement officer also observed that in countries like Nigeria and the Ivory Coast, many scammers often work alone. Though some may rely on support services (like logistics or money laundering), they typically develop and run scams independently, keeping the profits.

An example of a ‘demon’ was one case prosecuted by the Nigerian EFCC where the offender had defrauded a U.S. victim of $2,400 while posing as a woman in a romance fraud. There are many cases to be found like this.

Next is size there are Gorgons, named after the three-headed creature from Greek mythology, we use this term to refer to couples and small fraud groups under 10 often based upon small friend groups with role specialization—some lure victims, others extract money. In an example from 2024 in the UK, a couple were convicted of numerous romance frauds against international victims, transferring proceeds to Ghana.

In another example a Nigerian trio attempted to steal nearly $1 million via business email compromise (BEC) frauds.

Ogres are mythical giant creatures that eat people. Ogre is appropriate to link to the next category of groups of bad actors working together of less than 50, but more than 10. Ogres are found in West Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. A Ghanaian consultant described raids uncovering 30 people and 50 laptops in single rooms. In India, a bogus company with 36 staff scammed Americans via phone was discovered in a raid. In Nigeria, “Hustle Kingdoms”, have emerged that serve as fraud training centres with often dozens of trainees learning to and actually scamming.

Behemoth is a mythical large monster creature from the bible that causes chaos and is appropriate to describe larger enterprises. These terms describe the biggest groups of 50–250 and 250+ scammers. Precise numbers are hard to verify, but various raids and media reports reveal their scale. In India, a scam centre targeting Americans with fake IRS calls generated $300 million. Reports mention 630 staff and 197 arrests. Indian fraudsters described centres with 100–200 employees and aggressive sales incentives.

Southeast Asian scam compounds are massive. The UN estimates 120,000 are held in Myanmar and 100,000 in Cambodia for forced fraud work. A 2023 raid in the Philippines freed 1,100 people involved in crypto scams. These compounds operate like corporations, complete with dormitories, managers, security, and amenities. One Myanmar call centre had 294 staff.

In Nigeria, confraternities like Black Axe are large criminal organizations involved in fraud, money laundering, and more. Estimated to have up to 3 million global members, they are deeply embedded in universities and society. One Ireland-based Black Axe case involved thousands in romance and invoice frauds. Authorities identified 838 money mules, 63 herders, 50 directors, and 16 strategists. Behemoths are the most challenging groups of bad actors to emerge because of their size; they have immense capacity for inflicting harm and ample resources to protect themselves.

Larger scam operations exhibit high degrees of specialization. Like legitimate businesses, they employ recruiters, manipulators (“closers”), money launderers, IT experts, and even HR staff. In the U.S., past telemarketing frauds showed divisions of labor: frontline sales, closers, reloaders, and managers.

Indian scam centres have data sellers, trainers, and financial networks like hawala. Southeast Asian compounds have managers, “heavenly” (gambling) and “earthly” (investment) scam teams, HR, logistics, and services from barbers to brothels. West Africa’s Hustle Kingdoms have profilers, closers, money mules, and a leader (“Oga”). Nigerian confraternities operate in structured zones with chiefs, priests, enforcers, and treasurers.

A scamfighter noted that scammers specialize in initial outreach versus manipulation. Some groups run hundreds of fake sites at once, tailoring scams by geography—investment scams in Europe, employment scams in Asia, procurement scams in the U.S., and so on.

These groups also form international laundering networks, with members based in Europe, the U.S., and Canada. One Ghanaian official confirmed these global ties enhance the scale and reach of operations.

Indian centres may operate legally by day and shift to scams at night. One government official described these hybrid operations, while a scamfighter noted how some fraudsters also owned legitimate businesses like nightclubs to hide the operations.

Southeast Asian compounds and Nigerian confraternities represent the most complex, highly specialized and integrated scamming structures. As these organizations grow, so does their professionalization—mirroring the infrastructure and efficiency of legitimate enterprises.

The scamming ecosystem is also supported by corrupt actors who enable fraud, launder money, and help scammers avoid prosecution working in banks, regulators, law enforcement and prisons, to name some.

As the scamming ecosystem evolves in complexity and scale, so too must the tools and platforms fighting back. ScamAdviser, a foundation member at Global Anti-Scam Alliance (GASA), plays a crucial role in mapping the infrastructure of scams in real-time. Through the ScamAdviser Trust Score, the platform analyzes millions of websites daily, using AI and community reports to detect scam operations—many of which are part of the wider networks described in this article.

ScamAdviser’s open-access tools and threat intelligence not only help consumers avoid fraud but are also used by researchers, enforcement agencies, and cybersecurity companies to track digital fingerprints of scam networks, from lone “demons” to the sprawling “mega behemoths.”

In a world where many scam operations rival the size and complexity of multinational corporations, platforms like ScamAdviser help tip the scales—making scams harder to operate, easier to detect, and, ultimately, less profitable.

The global scamming industry is huge generating billions of dollars for the bad actors. Like any industry the range of scammers can be divided along size; ranging from the sole traders, the ‘demons’ to the large 250+ employee companies, the ‘mega behemoths’. The emergence of this global industry poses immense challenges to the anti-scam community, particularly the ‘behemoths’ as their potential for inflicting harm and using their extensive resources to protect themselves makes them difficult to confront. Indeed, in some countries the law enforcement capacity dedicated to tackling scams is smaller than some of these enterprises. Only global co-operation between law enforcement and the many private actors will work. This world is constantly changing and we have only started to grasp parts of this vast ecosystem, much more research is required to better comprehend it and to identify the weaknesses so these can be exploited by the global scam community.

This is a precis of a longer article currently under review written by Mark Button, Branislav Hock, Suleman Lazarus, James Sabia, Durgesh Pandey and Paul Gilmour. Research papers from this and related research can be found here https://www.markbutton.net/economic-crime/economic-criminals